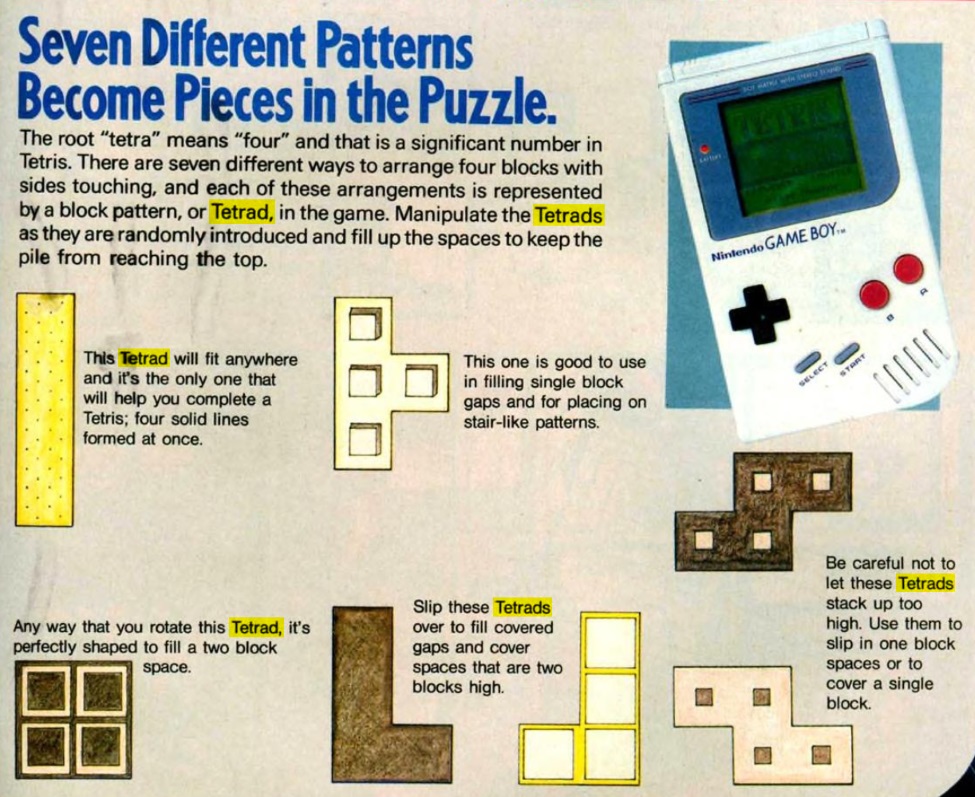

Around two years ago I encountered a very thorough blog post enumerating the many names for Tetris pieces, with extensive real-world usage examples demonstrating context-dependant use. The list includes:

- Tetrominoes (preferred by the creator, Alexey Pajitnov)

- Tetraminos (preferred by Vadim Gerasimov who ported Tetris to PC)

- Tetriminos (used in several official Tetris company publications)

- Tetrads (used repeatedly in Nintendo Power magazine)

- Blocks, shapes, pieces, and other generic words

Apparently this blog post stuck with me, because earlier this week I encountered a paper2 which refers to these pieces as "tetrazoids," and my immediate reaction was dismay at the fact that the Tetris terminology blog post had overlooked this particular variant.

Astonished by this terrible oversight, I proceeded to google 'tetris "tetrazoid"', looking for more usage examples. I found them, but with a twist: It appears that this term is exclusively used in academic literature related to cognition, perception, UX, and other fields in that ballpark3.

Why is this? The answer is fairly simple. Most of the mentions of tetrazoids (frequently shortened to "zoids") are in reference to one particular 1994 paper4 by David Kirsh and Paul Maglio.

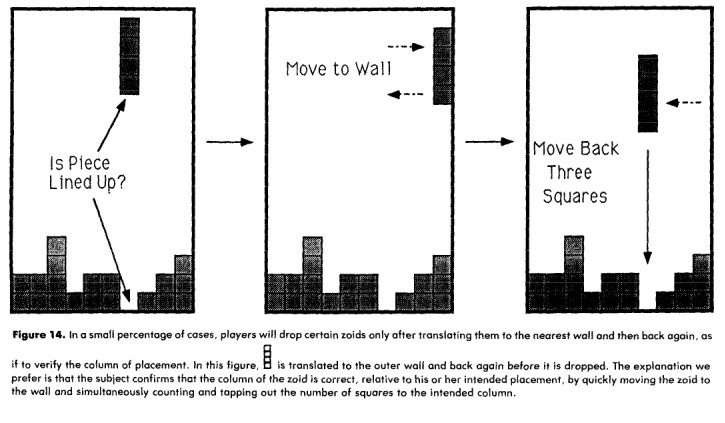

The only uses I can find predating this paper are by the same authors5. That being said, I found at least one6 "second-generation" use, by which I mean a use in a paper that does not directly reference Kirsh & Maglio. It's also interesting to note that this paper introduces the terminology by stating "we collected data on 39 features of Tetris play for each Tetris zoid (piece)", which suggests that the authors are probably aware that "piece" is a clearer term than "zoid", yet they use the word "zoid" anyways. We can even see this in Figure 27, taken from Kirsh & Maglio's paper, in which the caption says "zoid" but the image itself says "piece."

We are now left with the obvious question of where Kirsh and Maglio got the word "tetrazoid" from. I had some trouble figuring this out, and at one point I was seriously considering emailing one of them. Fortunately, I eventually found the answer to my question in the Acknowledgements section of Paul Maglio's PhD dissertation8, which mentions in a parenthetical that someone named Steve Haehnichen "coined the terms tetrazoid and RoboTetris."910

So, I guess the takeaway from this is that domain-specific terminology doesn't necessarily arise to fill a technical gap in the lexicon or for any other good reason; sometimes, researchers just use a colleague's invented word in a widely-cited paper and it ends up sticking.

- Image from the aforementioned [Tetris terminology blog post](https://meatfighter.com/tetristerminology/). ↩

- Liu, Zhicheng, Nancy Nersessian, and John Stasko. "Distributed cognition as a theoretical framework for information visualization." IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 14.6 (2008): 1173-1180. ↩

- The only easy-to-find exceptions are this tetris commercial which uses the word briefly as a joke, with an unclear referent, and this YouTube video where it's used as a joke alongside the equally unattested tetrazone. ↩

- Kirsh, David, and Paul Maglio. "On distinguishing epistemic from pragmatic action." Cognitive science 18.4 (1994): 513-549. ↩

- Kirsh, David, and Paul Maglio. "Reaction and reflection in tetris." Artificial Intelligence Planning Systems. Morgan Kaufmann, 1992. ↩

- Lindstedt, John K., and Wayne D. Gray. "Distinguishing experts from novices by the mind's hand and mind's eye." Cognitive psychology 109 (2019): 1-25. ↩

- Or Figure 14, depending on who you believe. ↩

- Maglio, Paul P. The computational basis of interactive skill. Diss. University of California, San Diego. 1995. ↩

- I don't know whether this is the same Steve Haehnichen who is apparently Qualcomm's director of engineering, but the city (San Diego) seems to match. ↩

- Also, at the time of writing, this dissertation is the only google result for 'Haehnichen "tetrazoid"'. ↩