Celeste is an extremely good indie platformer game. Much has already been written about its fluid controls, excellent soundrack1, and emotional resonance2, so I won't go into all that here.

I just want to point out some game design decisions that make the game's climax feel, well, climactic.

The Problem

Celeste is a game about a protagonist (Madeline) and a player (you?) struggling to climb a mountain (the mountain is a metaphor). Obviously, finally reaching the summit needs to feel special, like the culmination of a long and difficult journey.

But how do you achieve that without losing momentum across dozens of small "rooms," where the player is expected to die dozens of times before progressing? How do you make sure that the final room doesn't just happen at some point, resulting in an abrupt and unsatisfying conclusion?

The Solution

On the macro scale, Celeste does a lot to set expectations for Chapter 7 as something special and climactic. This starts with the level select screen:

It's not obvious from a single image, but this is actually the first time that we ever see the summit in-game! Before this point, the camera on the overworld map is always angled/cropped just right to keep it out of view3.

I suppose this could be a complete coincidence, but the ability to see the summit is used deliberately later (as I'll discuss), so I'd be surprised if this wasn't also deliberate.

This fits well with the narrative up to this point. Madeline has been struggling to climb the mountain throughout the entire game, but it's only after resolving her internal(ish) conflict that the summit is finally attainable. At this point in the story Madeline is physically further from the summit than ever before, but mentally ready to reach it.

Chapter 7 also starts with an animated cutscene graphic of Madeline looking up towards the summit, accompanied by the explosive opening bars of the chapter's high-energy soundtrack.

No other chapter starts with a cutscene graphic, so the choice to include one for Chapter 7 is clearly deliberate and significant. It further emphasizes the idea that the summit is finally in view, and starts the chapter off with a bang to recover any momentum lost during the chapter break.

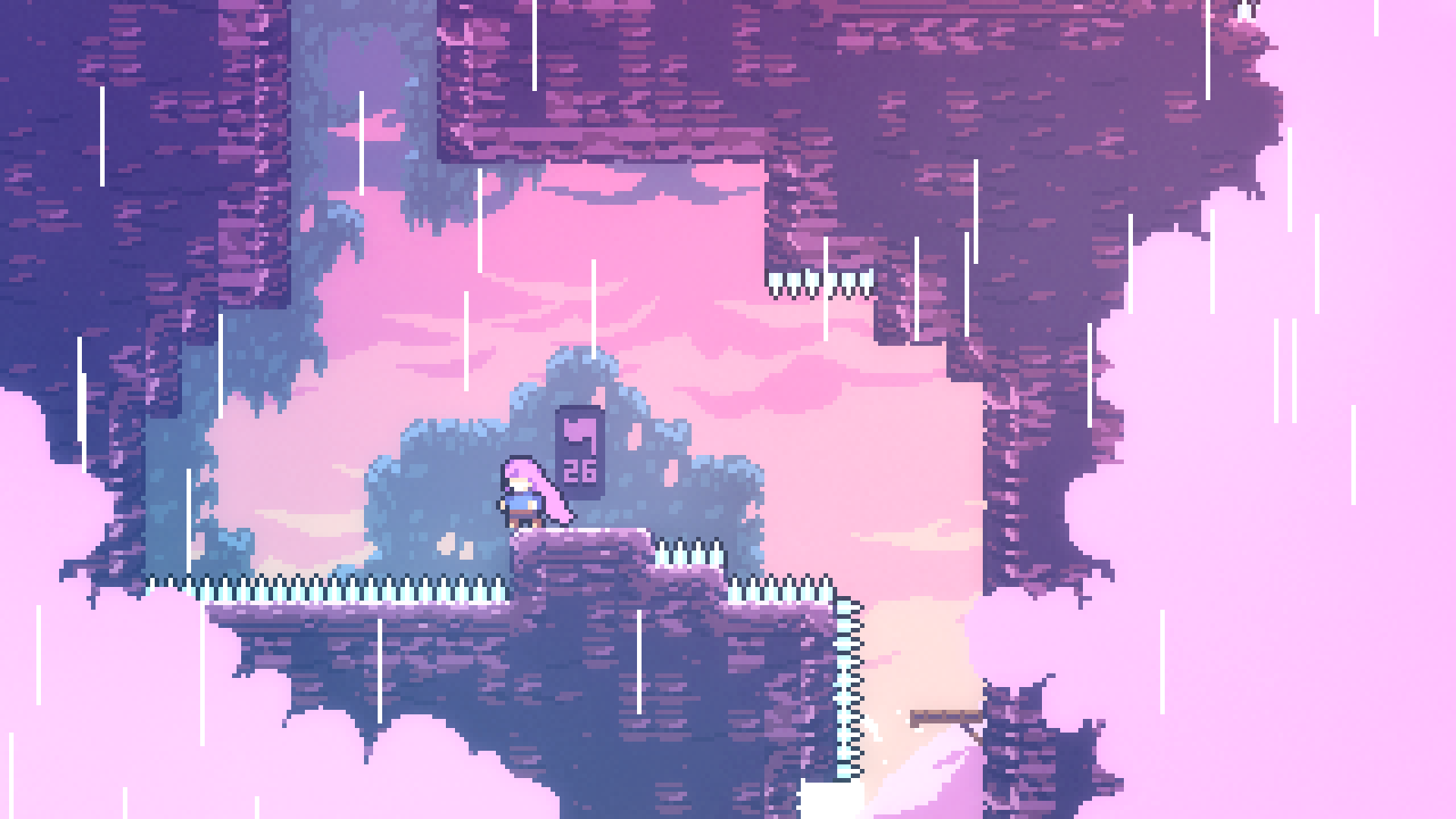

Zooming in a bit, Chapter 7 is divided into 7 sub-chapters. The aesthetic and mechanical design of sub-chapters 2 through 6 correspond to the first 5 levels of the game, so that over the course of Chapter 7 the player re-lives in miniature the entire process of climbing the mountain.

Most obviously, this helps to portray Chapter 7 as the culmination of the entire game up to this point. But perhaps more interestingly, it lets the player feel their progress within the chapter; there's always a sense of how much "closer" you are to the summit as you progress from one themed area to the next.

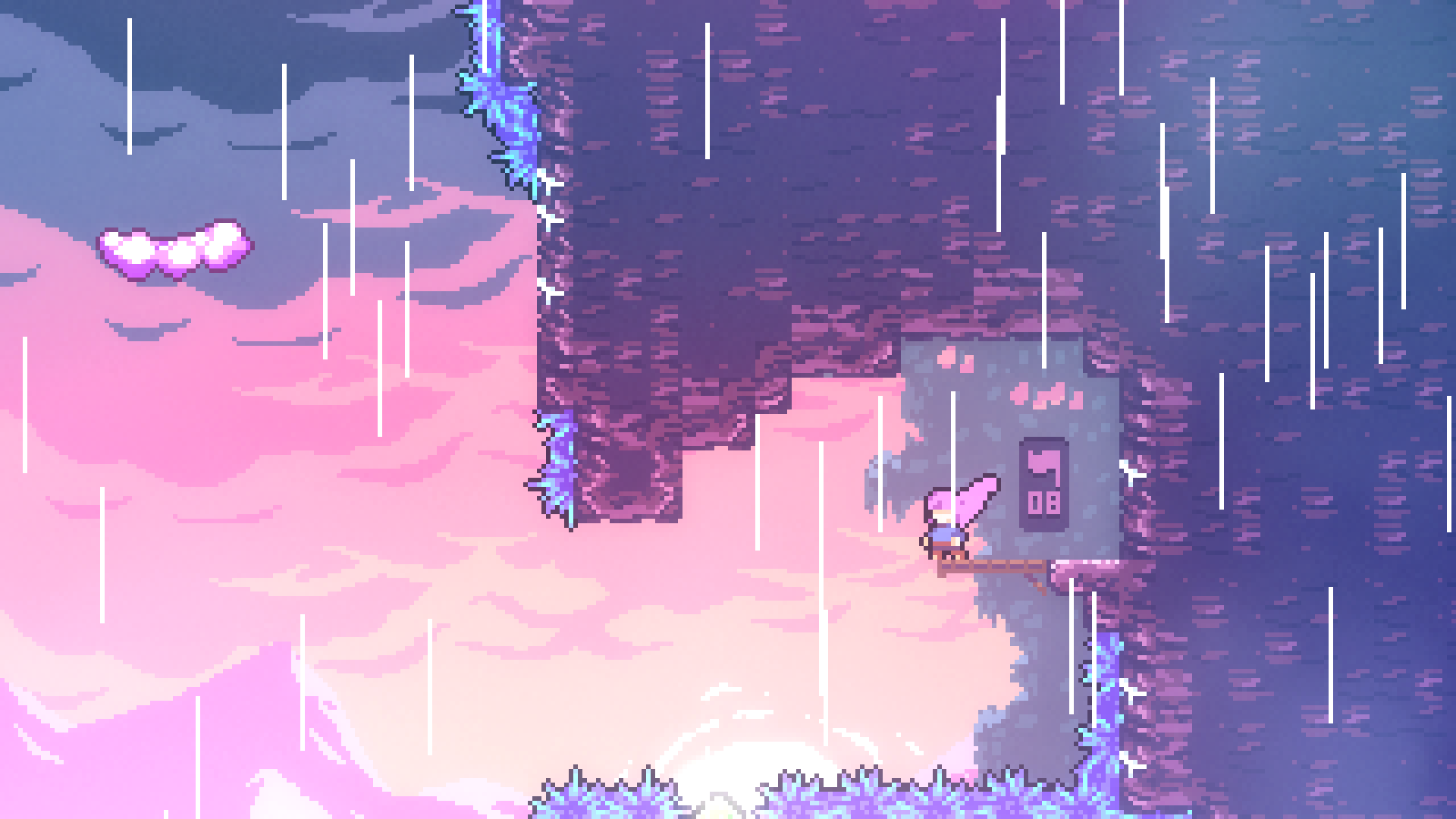

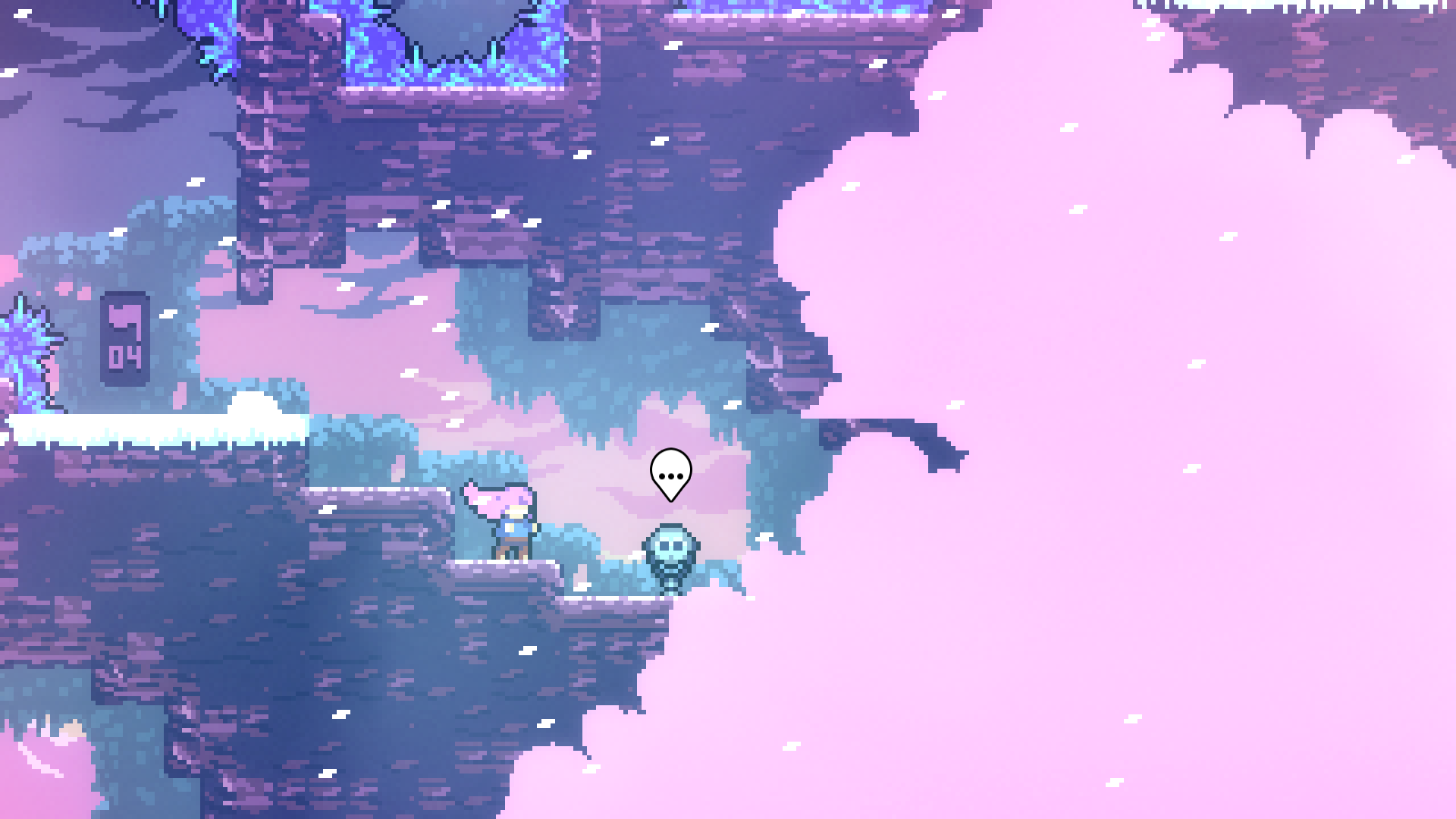

The theming becomes new and unique again in the final sub-chapter. At this point it's clear that we've reached the final stretch (and this is also explicitly confirmed through dialogue). But even within the final sub-chapter, a sense of progress and anticipation is maintained through the use of explicit signposts counting down the number of checkpoints left until the summit.

Finally, at the 4th-from-last checkpoint we find a pair of coin-operated binoculars:

Usually, these are used to let you look ahead to the end of a single room, which is useful purely for gameplay reasons. But this pair of binoculars is special, letting you pan ahead past checkpoint 3, past checkpoint 2, past checkpoint 1, and all the way to the summit. The camera zooms in and the music cuts out, leaving only the sound of the wind and the image of a flag waving on the summit.

It's yet another deliberate depiction of the summit being "finally in view," but on a micro-scale this time. I have a hard time imagining anyone quitting the game at this point; there's still at least one very difficult room left, but it really feels like you're too close to give up.

All of this ensures that the player knows exactly how close they are to the summit at all times, allowing anticipation to build up towards a specific, well-defined climactic moment at the end of the level.

Conclusion

I just think it's neat how Celeste deliberately and effectively uses the ability (or inability) to see the summit as a way to manage player anticipation and harmonize the intended emotions of the gameplay experience with the emotional arc of the narrative. It shows how much care went into every aspect of the game design.

- Listen to In the Mirror in reverse! ↩

- Check out the creator's thoughts exploring the complexities of authorial intent and how the game can describe a trans person's emotional struggles while also maintaining broader applicability. ↩

- except in the main menu screen, but I'm not counting that as "in-game." ↩